I follow a popular blogger who recently tweeted this travel tip: “You can’t understand the present if you don’t know the past. Read up on the destinations you are visiting.”

It’s a simple reminder that is extremely profound.

For that reason, I recommend that you read or listen to an audio version of Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, “The Long Road to Freedom” if you intend to visit Robben Island when you are in Cape Town.

Will it be emotional? Yes.

Will it also be educational? Yes.

Will it add depth and texture to your experience? Oh, yes!

(For this post, I decided to share excerpts from Mr. Mandela’s recollections of Robben Island that will help to provide greater context to your visit. It enhanced mine.)

___________

AT MIDNIGHT, I was awake and staring at the ceiling–images from the trial were still rattling around in my head–when I heard steps coming down the hallway. I was locked in my own cell, away from the others. There was a knock at my door and I could see Colonel Aucamp’s face at the bars.

“Mandela,” he said in a husky whisper, “are you awake?”

I told him I was. “You are a lucky man,” he said. “We are taking you to a place where you will have your freedom. You will be able to move around; you’ll see the ocean and the sky, not just gray walls.

He intended no sarcasm, but I well knew that the place he was referring to would not afford me the freedom I longed for.

That is how Nelson Mandela described the night he was told he was being moved to Robben Island – the stark, cold place that robbed him, and others, of simple freedoms many of us take for granted.

On the bus tour, I found out that in its heyday the island was ‘the most iron-fisted outpost in the South African penal system.’ It also served as a leper colony, an animal quarantine station and a hospital before it became known as a place of banishment and terror for activists opposed to apartheid.

We landed on a military airstrip on one end of the island. It was a grim, overcast day, and when I stepped out of the plane, the cold winter wind whipped through our thin prison uniforms. We were met by guards with automatic weapons; the atmosphere was tense but quiet.

I was bundled up when I stepped off the ferry – in sweater and scarf with long jeans – and the brisk wind still gave me goose bumps. I can’t begin to imagine what Mr. Mandela and his colleagues must have felt when they landed that day and were stopped to be processed.

We were driven to the old jail, an isolated stone building, where we were ordered to strip while standing outside. One of the ritual indignities of prison life is that when you are transferred from one prison to another, the first thing that happens is that you change from the garb of the old prison to that of the new.

The prison was divided into two distinct areas. There was the general prison, known as sections F and G, which contained communal cells, and a quadrangular shaped area with single cells known as sections A, B, and C. Those cells and a guard station bordered a courtyard. Mr. Mandela was placed in cell 466 on Block B. Each cell was outfitted with a bucket, a cup, one dish, and a blanket. There were no pajamas issued, and none of today’s basic prison necessities like bunk beds or sheets.

Apartheid’s regulations extended even to clothing. All of us, except Kathy, received short trousers, an insubstantial jersey, and a canvas jacket. Kathy, the one Indian among us, was given long trousers. Normally Africans would receive sandals made from car tires, but in this instance we were given shoes. Kathy, alone, received socks. Short trousers for Africans were meant to remind us that we were “boys.”

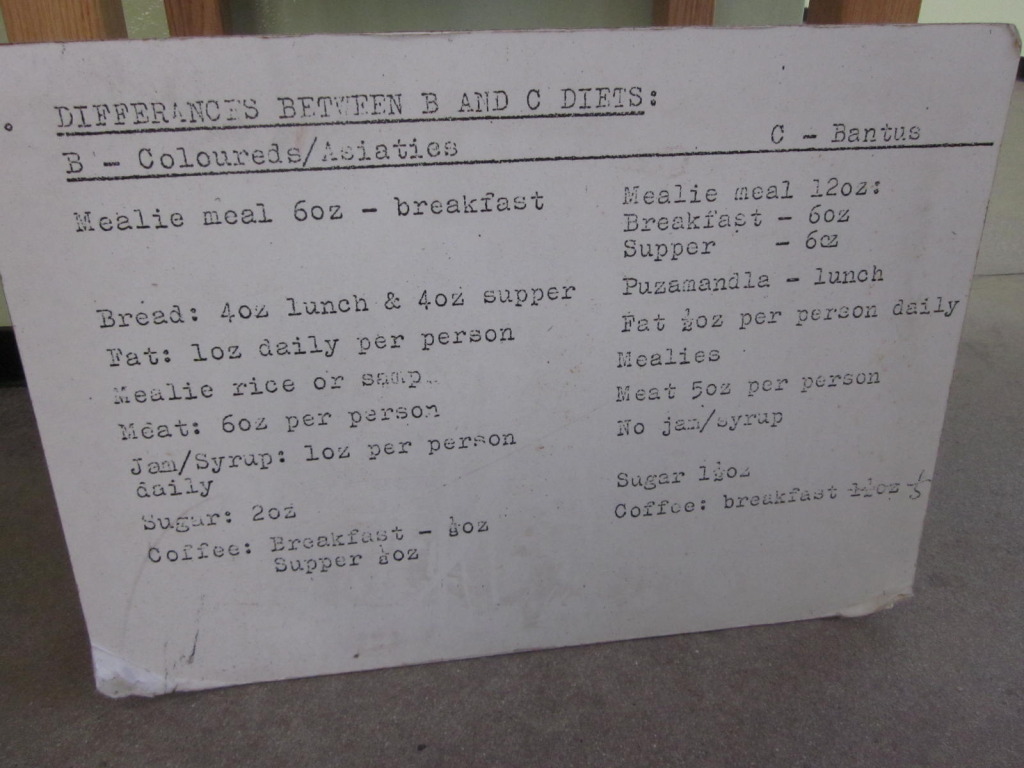

Our tour guide, a former political prisoner himself, explained that there was differential treatment for other things as well. Meals, for example, varied for blacks and coloreds. (Only Africans and Indians were sentenced to spend their terms on Robben Island; women and Caucasians were sent elsewhere). Persons also were placed into one of four categories: A to D. Those in groups A and B were allowed four letters per month while the Cs and Ds only got one.

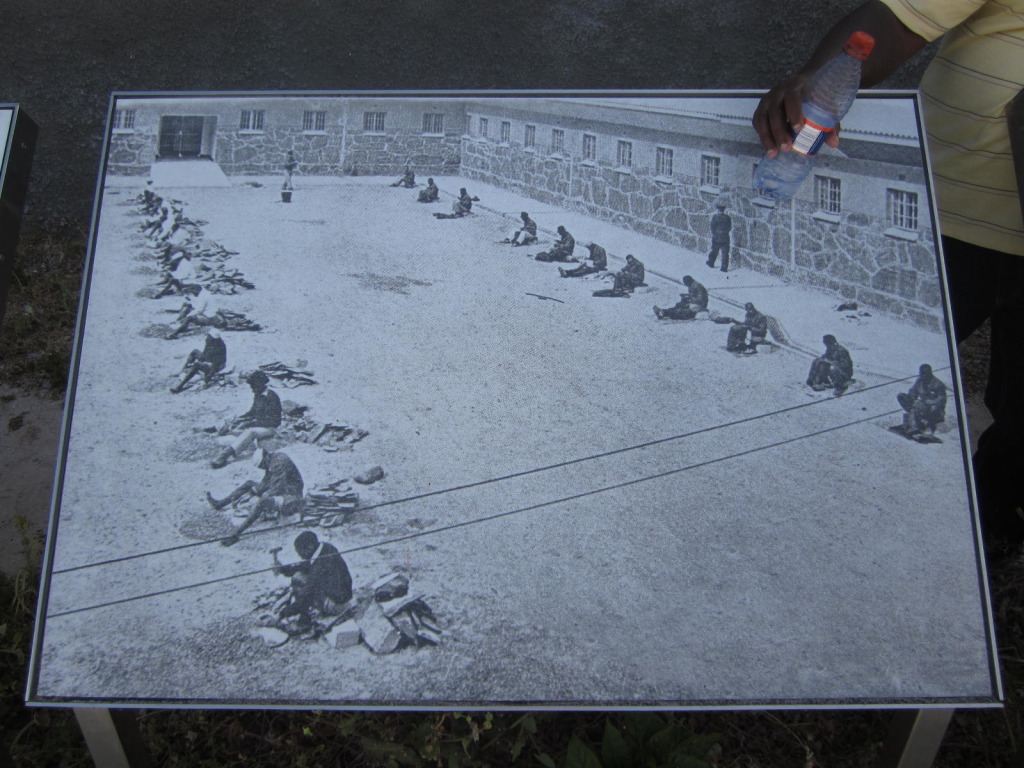

That first week we began the work that would occupy us for the next few months. Each morning, a load of stones about the size of volleyballs was dumped by the entrance to the courtyard. Using wheelbarrows, we moved the stones to the center of the yard. We were given either four-pound hammers or fourteen-pound hammers for the larger stones.

Our job was to crush the stones into gravel. We were divided into four rows, about a yard-and-a-half apart, and sat cross-legged on the ground. We were each given a thick rubber ring, made from tires, in which to place the stones. The ring was meant to catch flying chips of stone, but hardly ever did so. We wore makeshift wire masks to protect our eyes.

The guide told us that the task gradually advanced to eight hour days spent breaking stones in a limestone quarry. Prisoners were exposed to all elements of weather, and forced to work with the most primitive of tools under the supervision of 15 guards who had dogs. Many ended up with permanent eye damage because of the harsh glare of the sun and the ever-present stone particles.

On occasion, the men would relieve themselves in a small cave at the back of the quarry. It was the only place that they could escape the watchful eyes of the guards. We were told that they also carved out time to teach each other how to read and write in the dirt there. It became known as their ‘prison university’ and ‘informal parliament’. I’ve since read that it is quite possible that a significant portion of South Africa’s current constitution was written in that cave.

Other noteworthy tidbits that I gleaned from the tour are listed below.

- Wardens were replaced at regular intervals because some of them were swayed by the arguments

- Prisoners in the communal cells slept on the floor and often huddled together for warmth on cold winter nights

- Baths were allowed twice per week only; on Wednesdays and Sundays

- Prisoners with blisters were not attended to by doctors yet they could not complain. They were forced to use every means possible, including the ammonia from their own urine, to try to achieve healing

- Hot water and bunk beds in the communal area were not available until after increased pressure from the outside world

- Today, only former inmates serve as guides for the prison segment of the tour

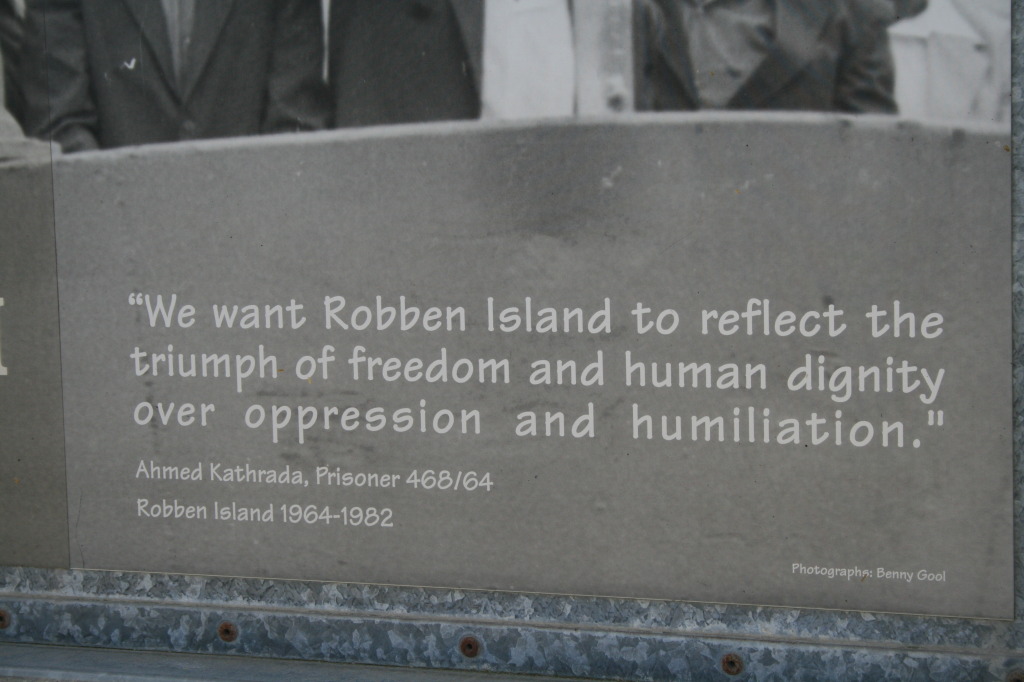

Given what you see and hear on the island, it would be easy to walk away from Robben Island a bitter, sad, or heavy-hearted individual. But thanks to Mandela’s unifying spirit, and the outlook of many of his fellow prisoners, you leave instead humbled and grateful for their sacrifice. The sign at the entrance and exit best sums up the legacy of Robben Island. It is pictured below.

Tata Mandela himself later expanded on that sentiment even more:

“While we will not forget the brutality of apartheid, we will not want Robben Island to be a monument of our hardship and suffering. We would want it to be a triumph of the human spirit against the forces of evil, a triumph of wisdom and largeness of spirit against small minds and pettiness. A triumph of courage and determination over human frailty and weakness.”

________

Editor’s Notes:

To get to Robben Island, you take a ferry from at the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront in Cape Town. Look for the Nelson Mandela Gateway that houses a museum shop, a restaurant, and a multimedia exhibition.

The boats leave on the hour between 9am-3pm, and the journey can take anywhere between 30 minutes to an hour depending on the weather. When you arrive on the island, you are taken on a bus tour that passes by the Lepers’ Graveyard and the tiny house where another famous political inmate, Robert Sobukwe, lived in solitary confinement for several years. He was the only prisoner who was allowed to smoke, and he died of lung cancer at the ripe old age of 54.

You also get to see two of the oldest buildings on the island; the Irish church built in 1841, and the lighthouse that was built 25 years later. There is also a guest house where President Clinton and his wife stayed when they visited with Mr. Mandela in the late 90s.

Of course, there is also the obligatory gift shop. Allocate about three and half hours for the complete tour.